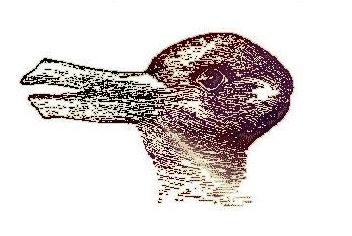

Is it a duck, or a rabbit?

Peter Van Inwagen's contribution to

God and the Philosopher's, "Quam Dilecta", is impressive. I'm still mulling it over. The title means, roughly, "How lovely!" and is taken from Psalm 84.

For now, here is a bit in which he describes a transitionary period in his life - a movement from Naturalism to Naturalism

plus.

I shall try to describe three of these "episodes of thought." First, I can remember having a picture of the cosmos, the physical universe, as a self-subsistent thing, something that is just there and requires no explanation. When I say a "having a picture," I am trying to describe a state of mind that could be call ed up whenever I desired, and which centered round a certain mental image. This mental image--it somehow represented the whole world--was associated with a felt conviction that what the image represented was self-subsistent. I can still call the image to mind (I think it's the same image) and it still represents the whole world, but it is now associated with a felt conviction that what it represents is not self-subsistent, that it must depend on something else, something not represented by any feature of the image, and which must be, in some way that the experience leaves indeterminate, radically different in kind from what the image represents. Interestingly enough, there was a period of transition, a period during which I could move back and forth at will, in "duck-rabbit" fashion, between experiencing the image as representing the world as self subsistent and experiencing the image as representing the world as dependent. I am not sure what period in my life, as measured by the guideposts of external biography, this transition period coincided with. I know that it is now impossible for me to represent the world to myself as anything but dependent.

The second memory has to do with the doctrine of the Resurrection of the Dead. I can remember this: trying to imagine myself as having undergone this resurrection, as having died and now being once more alive, as waking up after death. You might think it would be easy enough for the unbeliever to imagine this--no harder, say, than imagining the sun turning green or a tree talking. But--no doubt partly because the resurrection was something that was actually proposed for my belief, and no doubt partly because I as an unbeliever belonged to death's kingdom and had made a covenant with death--I encountered a kind of spiritual wall when I tried to imagine this. The whole weight of the material world, the world of the blind interaction of forces whose laws have no exceptions and in which an access of disorder can never be undone, would thrust itself into my mind with terrible force, as something almost tangible, and the effort of imagination would fail. I can remember episodes of this kind from outside. I can no longer recapture their character. I have nothing positive to put in their place, nothing that corresponds to seeing the world as dependent. But I can imagine the resurrection without hinderance (although my imaginings are no doubt almost entirely wrong), and assent, in my intellect, to a reality that corresponds to what I imagine.

The two "episodes" I have described were recurrent. I shall now describe a particular experience that was not repeated and was not very similar to any other experience I have had. I had just read an account of the death of Handel, who, dying, had expressed an eagerness to die and to meet his dear Savior Jesus Christ face to face. My reaction to this was negative and extremely vehement, a little explosion of contempt, modified by pity. It might be put in these words: "You poor booby. You cheat." Handel had been taken in, I thought, and yet at the same time he was getting away with something. Although his greatest hope was an illusion, nothing could rob him of the comfort of this hope, for after his death he would not exist and there would be no one there to see how wrong he had been. I don't know whether I would have disillusioned him if I could have, but I certainly managed simultaneously to believe that he was "of all men the most miserable" and that he was getting a pretty good deal. Of course this reaction was mixed with my knowledge that the kind of experience I tried to describe in the preceding example would make Handel's anticipation of what was to happen after his death impossible for me. I suppose I regarded that experience as somehow veridical, and that I believed that Handel must have had such experiences, too, and must have been trained, or have trained himself, to ignore them.

If you're not doing anything important, the entire essay is

available here. It's not a quickie, but it is very thoughful and I enjoyed the heck out of it.

Duck-rabbit. That image of one of those psych pictures that alters betwen two views is a really good way of capturing how one's mind breaks free from Naturalism's grasp. Surprisingly too, Inwagen is right. It does become more difficult to recall the other view as one becomes comfortable with the new.

Is it a duck, or a rabbit?

Peter Van Inwagen's contribution to God and the Philosopher's, "Quam Dilecta", is impressive. I'm still mulling it over. The title means, roughly, "How lovely!" and is taken from Psalm 84.

For now, here is a bit in which he describes a transitionary period in his life - a movement from Naturalism to Naturalism plus.

Is it a duck, or a rabbit?

Peter Van Inwagen's contribution to God and the Philosopher's, "Quam Dilecta", is impressive. I'm still mulling it over. The title means, roughly, "How lovely!" and is taken from Psalm 84.

For now, here is a bit in which he describes a transitionary period in his life - a movement from Naturalism to Naturalism plus.

Comments